THE IGNORED ONES

In a society that functions in a balanced way and that protects all components of its population in the same way, the pandemic should not cause the hunger queues like the ones we have been seeing in Spain during pandemic. If they appeared, it is because there are deeper problems that condemn certain segments of the population to a more acute vulnerability in situations like the one we are experiencing. At the social level, what the pandemic seems to demonstrate most strongly is that a significant percentage of the population lives in a situation that does not guarantee them resources even for a month of confinement. A confinement carried out in conditions that allow maintaining a decent standard of living was unattainable or almost a luxury for many.

In Spain the submerged economy flourishes and is one of the most developed among European countries. Many people live on the margins of society depending on precarious jobs, largely feminized or racialized and not recognized socially and / or legally, despite the fact that these jobs are essential for good functioning of whole country. Cleaners, caregivers or day laborers are some of the most striking examples. Many of these people also live in an administrative situation that conditions the development of their life projects, preventing them from accessing safe jobs in decent conditions.

During the confinement, many of these people were excluded from any institutional help or support, unable to even submit a subsidy application. Others, in the process of regularization, were left in limbo, since all administrative procedures were suspended.

Many of these people were also forced to go to the solidarity food pantries, set up by neighborhood networks that have so far saved a multitude of families from the risk of hunger and acute social exclusion. Without salaries or rights to benefits, unemployment or ERTE*, these people often had to choose between paying their rent or buying food.

To respond to the emergency and meet the most basic needs of these people, neighborhood networks and various neighborhood organizations launched a series of solidarity initiatives. From food pantries, through a network of volunteer interpreters who facilitated the care of immigrants in health centers, to support against the risk of evictions and the fight against the digital gap that, in times of pandemic, had disastrous consequences in terms of access to aid and administrative procedures.

*ERTE - Temporary Employment Regulation - is a measure approved by the government in Spain during the pandemic to protect jobs from layoffs.

“I am not afraid to say that I work in black, let's see I have colleagues who are Spanish and who work in black too. The submerged economy in Spain is impressive because many employers do not want to pay social security…. Now I am asking for papers, based on my social roots here and showing that there is an employer who wants to hire me. But you can do this only after having lived in Spain for 3 years. Living here for three years without papers allows you to launch the procedure. But how you lived during these three years and with what money, nobody asks you. And tell me, who comes to Spain with enough savings to live for so long? In such a system, it is normal for people to work in black."

Andrea (43 years old, Chile)

Degree in Mining Engineering; works in a hotel in Madrid

Degree in Mining Engineering; works in a hotel in Madrid

To read more about the “Regularization Now" campaign (in Spanish): ENTER HERE

STORIES

ANDREA (43 years old, Chile) has a 6 years old daughter. She arrived in Spain 5 years ago. In Chile she worked in the Mining Engineering sector. She has two university degrees completed and a high level of English. Here she works as receptionist at night in a hotel, but so far without legal permit.

Spain is one of the countries that top the European Union lists in terms of the importance of the underground economy. Apart from all the negative consequences that the lack of regularization has, in this pandemic, in addition, people who are forced to work in informal economy, were left without resources or the possibility of requesting any institutional aid... READ MORE

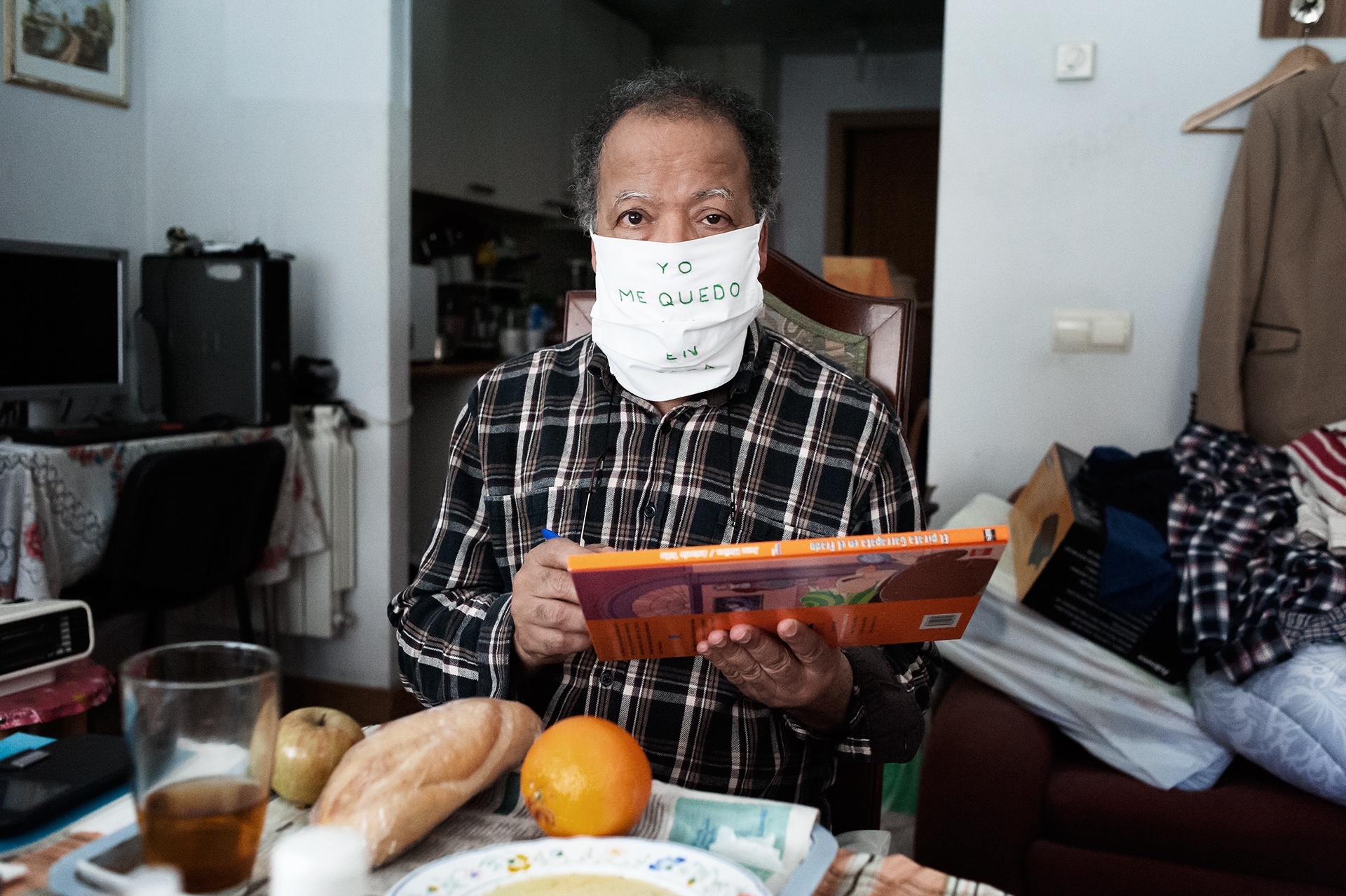

MOHAMMED is 74 years old. 12 years ago he came to Spain on a tourist visa. Someone proposed him a job as a street advertising deliveryman, paying € 100 a week. As Mohammed says: “In Morocco it is a lot of money. With this I could live normally, and send money to my family”. In Morocco he has his wife and two children. Her oldest son also lives in Spain, working as a caregiver for the elderly people.

Mohammed tried to fix his administrative situation. He asked for papers alluding to his roots in society but he got a negative answer .... READ MORE

Mohammed tried to fix his administrative situation. He asked for papers alluding to his roots in society but he got a negative answer .... READ MORE

ARACELI (63 years old, born in Mexico) grew up and spent much of her life in the United States and Canada. Since 2000 she has been living in Spain. She always looked for life in her own way and since being in Spain she has tried to get various jobs - from a teacher and / or English translator (she is bilingual) to an administrative position. But as she says: "here, if you don't have a diploma, your experience, no matter how long, is worthless."

To eat, Araceli goes every day to the social food center and once a week to the solidarity pantry ... READ MORE

“I need legal papers to be able to live normally and to be able to go to Morocco to see my wife. I've only seen her through video calls for the last 12 years. I would like to go back to Safi, but I have to stay here and look for whatever kind of job, so I can help them. Life is very hard there."

Mohammed, user of the solidarity pantry

in La Villana de Vallekas

in La Villana de Vallekas

THE HUNGER TAILS

The pandemic has many faces and leaves long-term consequences. In Madrid, as in other places, during confinement the spectrum of hunger was getting bigger and bigger. Many people found themselves faced with a dilemma of being able to eat or pay the rent. The hunger lines, which appeared almost at the same time that the state of alarm was decreed, did not stop growing and, a year later, many people still need help to be able to eat.

Faced with this food crisis, several self-managed centers, associations or simply neighborhood residents launched solidarity and voluntary initiatives to help meet basic needs such as food, cleaning products, diapers for children. This network of solidarity pantries soon had to start offering other types of aid - school support and search for equipment so that the children of the most affected families could continue studying online.

Often, affected people who saw for the first time a need to ask for food, became involved in the preparation of baskets and distribution of food, in order to return to others the help they received. The solidarity network between neighbors grew, without public institutions adequately supporting this essential work. On the contrary, social services, often overwhelmed by the situation and the growing demand, send the people affected towards voluntary neighborhood networks.

The list of centers and associations that developed this type of aid in Madrid is long. Below you can find information about some of them (in Spanish):

...

“Think that there are people who haven't worked for a month and don't even have enough to eat! In what conditions were they living before so that when they don't work for a month, they don't even have enough savings to eat? Are we living so much up to our necks? In this land of freedom? It makes you think…. And we don’t speak about few people only…"

Mikel, volunteer of the solidarity pantry

La Horizontal, Vallecas (Madrid)

La Horizontal, Vallecas (Madrid)

La Horizontal is one of these self-managed centers that practically from the beginning of the pandemic launched a solidarity network for the collection and distribution of food to those most in need. Each time the queue grew larger and the neighborhood network was quickly overwhelmed by demand. All the more so that the social services of Madrid, also overwhelmed and with few resources due to lack of an adequate institutional response, brought people down to solidarity pantries in neighborhoods such as La Horizontal.

The pantries in general functioned on the basis of voluntary work and donations, both from individuals and small businesses. The whole question is how long this solidarity network will last, taking into account that this crisis will leave its marks in the long term.

“Some people believe that after the pandemic the need will end, but this neighborhood (Vallecas) has permanent precariousness and since the crisis of 2008 it cannot be said that it has disappeared. There are people who are precarious even if they have a job, and if they don't have it, their situations is even worse.

Even in my building, around three days after the state of alarm was decreed, on my portal I found a girl crying. A neighbor of mine had her as an intern caregiver and had her without a contract, and has thrown her out on the street in the middle of pandemic. And the girl found herself without a job and a house at the same time, without legal papers and without any help. The house care sector is the one that suffered the hardest shock in this pandemic.

What will happen when we stop to distribute food? I do not know, there are other places, but what they do is not enough, otherwise there would not be so many people who go to the pantries. But for me personally, what I like about our initiatives is that we try to build synergies, so that people get involved in the way that we can only solve problems together." – Mikel

...

...

“What I bring from the social kitchen and from the solidarity pantry, I share with an older woman who has lived alone for two years. She ran away from home because her husband abused her, and she is still afraid to go out, in case he finds her.”

Araceli, user of the solidarity pantry

in La Villana de Vallekas

...

...

“I don't want help from the government, I want to work! Why don't they let me work? It's the worst ... there is a great need, in the fields, in the markets, cleaning houses or cooking. But without papers I can't do anything. Now we need to work to pay rent and eat, then I'll think about my career.”

Flavio (34 years old, Brazil)

Flavio y Nivaldo, a gay couple from Brazil, arrived in Spain in December 2020 with the intention of seeking asylum. In Spain, during the first 6 months, asylum seekers have no right to work or to ask for any kind of help. They have to endure. Flavio and Nivaldo arrived with savings that they thought were sufficient, they even invested in language classes to prepare as best as they could for their new life. But finally the expenses turned out to be higher than they thought and last month they faced a dilemma: pay the rent or buy the food ... READ MORE

Johan & Zulail

(Venezuela)

(Venezuela)

Johan and Zulail (28 and 27 years old respectively) arrived in Spain in 2017. They applied for asylum and after a long wait they managed to obtain their papers. But stable work with a contract is another problem.

Johan went from one short-time job to another, always in the construction sector. The last one ended just before the state of alarm was declared, at the beginning of February 2020, with which he was unable to benefit from aid for those who lost their jobs due to the pandemic. Nor can he get another job, since in time of confinement the company was closed. He did not have the right to ERTE* and neither to unemployment benefit, since he did not contribute enough to the Social Security System, as most of the jobs was able to get was on black and without contract.

Zulail used to work in a bar as a waitress. She got pregnant and at one point it started to be more difficult to carry on so her boss put her on cleaning. They paid her €5 an hour, but registered her at the Social Security System only at the end and at part-time, although in reality she worked longer hours. She endured cleaning at night until practically two weeks before giving birth and gave birth two days after the declaration of the state of alarm. As her employer has not contributed much for her, she was left with nothing, not even having the right to maternity leave.

They live with their two children (the newborn and a 5-year-old girl) in a 60m2 flat that they share also with Zulail's parents and Zulail’s younger brother Rojelio. In Venezuela, Zulail's parents worked in a school, in cleaning and maintaining jobs. The salary was very low and the crisis was felt more and more strongly. But what finally convinced them to leave was that fact the army wanted to take away the youngest son Rojelio. The mother decided to take him out of school and take him with her to Spain. Months later the father came, arriving practically just before the pandemic.

In Spain, Zulail's mother worked as a domestic caregiver, taking care for elderly people. She finished the job in December and, as the pandemic started, she could not find anything else. As she has been in Spain less then one year, she had no right to any institutional help. Rojelio used to work in small part-time jobs in fairs. Nobody wanted to contract him legally so he worked on black. With the confinement this sector also collapsed and Rojelio, like the rest of his family, was left without income.

During the state of alarm the family was living on savings and thanks to the fact that the owner of the apartment agreed to collect only part of the rent during the confinement. But even so, without income, the little savings they had could not provide for 5 adults and two children for a long time. They tried to contact social services, but they were told that they were not entitled to any kind of subsidy and gave them only a box of food. They also contacted the Red Cross, where they have been told that everything is collapsed and that they will be contacted back at some point. Two months later they were still waiting. They heard about a solidarity pantry in a center of the neighborhood (La Horizontal) and there they were able to collect some boxes of food and basic cleaning products for their baby.

The state of alarm and lockdown found many families trapped in small and over-occupied apartments; without resources or aid. For them, confinement in conditions, respecting all the hygiene requirements imposed by this pandemic, was an unattainable luxury. - “If I have to ask for boxes of food in pantries, how do you want me to buy masks, gels and everything they say is necessary? If a box of masks costs €50, do you know how many kilos of rice I can buy with that and feed my family?”- Johan.

*ERTE - Temporary Employment Regulation - is a measure approved by the government in Spain during the pandemic to protect jobs from layoffs.

JOINING FORCES

The organization World Central Kitchen was created by José Andrés a famous Spanish chef based in the United States. The organization arrived in Madrid in the middle of the pandemic, around March 20, to respond to the food emergency that was hitting the city, starting with the preparation and free distribution of some 950 free menus a day. At the end of May they were already distributing almost 13,000 daily free menus. The number was growing and the organization opened its kitchens in other cities too.

All work is done on a voluntary basis, while food and cooking expenses are covered by donations from around the world. The only thing that the organization received from the public institutions of Madrid was the transfer of the facilities of the Municipal School of Hospitality (in Santa Eugenia), but with energy supplies and similar bills are covered by the WCK.

To assess the daily need for menus, the NGO collaborates with the Food Bank, associations, parishes and even the Red Cross. A part of the menu distribution is provided by the NGO itself, which used vans rented and paid for by it. The rest of the distribution is made through the associations and above all thanks to the firefighters, who goes out voluntarily every day to bring meals to those most in need.

THE DIGITAL GAP

The pandemic is profoundly transforming the way we function and some of these transformations may, at least partially, produce more lasting changes. One of them is to transfer most of our activities online.

Work, shopping, cultural activities, administrative procedures and especially teaching were transferred to the virtual world to avoid direct contact and infections. At certain times it was the best solution, without evaluating possible problems that this digitization may create.

In our society it is taken for granted that we all have the Internet, Smartphone, computers or tablets at home. But it is not true and during the pandemic many families, especially those who already lived in a precarious economic situation before had to face problems due to not being able to access various benefits, education or work online.

In the case of education, the consequences of this digital gap are all the more important that they produced an additional delay, especially among children who are already disadvantaged, coming from poorer or marginalized families. For their part, the schools were unable to provide all of these students with the tools that would allow them to follow the courses online. Especially in the case of public schools, already very affected by previous cuts and with little funding. Once again, those who responded to this digital crisis were the solidarity networks of neighbors. In many self-managed centers, in parallel to the food pantries, school help and a search for second-hand computers or tablets were developed.

Among certain segments of the population, such as the elderly, migrants or employees of the domestic sector, the digital gap made it difficult to access much-needed services. Many of these people were unable to obtain appointments in health centers, access social service benefits, or apply for subsidies. One of the most striking examples is the case of domestic workers* who, without access to a stable connection, computer and scanner, could not make a request for extraordinary allowance to alleviate the loss of their job during confinement.

*To know more about the situation of domestic workers: ENTER

"I love learning something new, I like novels that are like a movies but written ones, but when I'm a little lazy, I also like comics."

Lidia, 10 years old

“I want my girl to study. I always push her to study. So in the future, she can telework and earn a better living."

Enriqueta, 50 years old

Enriqueta lives in a small 40m2 house. In two tiny rooms have to fit a total of 5 people: Enriqueta shares one with her 10-year-old daughter Lidia and the second one is occupied by Enriqueta's son, his wife and their one-year-old baby. During the confinement Lidia, without a computer and stable Internet connection, could not study. While other children received their homework and progressed online, Lidia waited accumulating delay that she will have to make up on her own. In this house, the online school was a dream that Lidia was only able to access at the end of the confinement, and thanks to the generosity of a man who, moved by the family's situation, gave her a second-hand computer ... READ MORE

...

HOUSING

When confinement turns out to be a luxury

Jess (32 years old, Mexico) came to Spain 4,5 years ago, with the idea of spending about three months working in Ibiza, saving money and then heading to Switzerland. But once here, life took many turns and, although he never discarded his Swiss dream, for the moment he is still on Madrid soil.

Since he arrived, he sought life as best as he could. He has no papers, but he works nights attracting clients for bars and discos and rents a small room in a shared flat. The room was nothing to write home about: barely 5m2 and no window for about €370 a month, but well located and Jess was happy enough with it. During the confinement he lost his job. Without much savings or salary, he could not pay the rent and the owner did not want to hear about delay.

The more than 3 years during which Jess religiously paid his rent were weightless. The constant reminders of payment quickly turned into threats: - “She would send me messages and sometimes she would come knocking on my door saying: - you are undocumented, you have no papers, the police will come for you because you have nothing…. I'm going to kick you out of my apartment, I'm going to kick you out to the dogs, you're going to shit in there ... – I could no longer bear this harassment.” ... READ MORE

...

HEALTH

When the universal healthcare doesn't go for everyone

“More and more people call me, and I can't not to help them even if I'm at work. It is a matter of health and it can be a matter of life. When the case of Mohamed came out in the media, there was a lot of noise and so they hired a company to have interpreters (Dualia - h.j). But the company is in Andalusia, everything is done by phone and the problem is that you can hardly ever contact them. Also this company does not have a Bangla interpreter, no matter how often they repeat they have it, it is not true, or at least I do not see it. Social workers, doctors, nurses who cannot reach this company finally call me for help. I can continue doing it, but of course, sometimes I spend half an hour on the phone just taking care of one person's case. I work well, but I am afraid that my boss will one day get tired of all this and throw me out."

Manik (36 years old, Bangladesh, volunteer interpreter).... READ MORE

...

Project realized with a support of a grant from the European Journalism COVID-19 Support Fund